Introduction

This paper is about the French painter and conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp, who created a series of very influential conceptual event-objects. In the beginning of the twentieth century he shocked and revolutionized the artworld. He did so with art objects trying to capture the phenomenon of motion and with already fabricated, found objects, called readymades, with which he poked and broke through the boundaries of what even the avant-garde in his days accepted as art. His influence was wide and enduring. New York Dada, Surrealism, installation art, Pop Art and conceptual art were all movements in which the contours of his shadow could be recognized even to the extent that one can study now a wide-ranging Duchamp Effect and study how, when and why that came about. This paper will not focus on the Duchamp effect but on the Duchamp cause as a necessary ingredient of understanding Duchamp’s influence throughout the twentieth century and beyond. Therefore, if the question at hand is: “Is there a Duchamp Effect?”, then a really rigorous answer to that question will first have to establish what we mean with the idea “Duchamp Effect” by looking at the “Duchamp Cause”. In other words, and this will be my specific research question, what was it precisely that Duchamp did with, through, for and against art, such that we can then recognize and assess how other artists, both with and after him, could appropriate and expand on his innovations and how other writers could develop reasonable or unreasonable re-interpretations and critiques of his gestures.

Because of some training in phenomenological methodology obtained during a previous stint of classes which I took ten years ago at Northern Illinois University under the Heidegger expert Dr. Theodore Kisiel, I could quite easily see, not only that Duchamp’s radical experiments with art could be better understood from within the phenomenological framework, but also that Duchamp himself was applying, in an implicit, spontaneous manner, the very same tools which underlie phenomenology. After refreshing myself with some of the basic readings in phenomenology, especially regarding aesthetics, I could easily see the fruitfulness of letting Duchamp and phenomenology interact. On that basis I can formulate an initial answer to my research question, which is as follows:

In his artistic accomplishments Duchamp applied in a naive, non-formal manner several techniques explicitly developed by the German philosopher and founder of the phenomenological school of philosophy Edmund Husserl. Duchamp did this especially through a) the ‘bracketing’ or ‘suspension’ of hitherto unquestioned assumptions regarding art (epoché) and b) by the application of ‘imaginative free variation’ (eidetic reduction) on many explicit and implicit aspects of art. These non-formal techniques enabled Duchamp to a) radically question the assumptions underlying the phenomenon art; and b) thereby opening up new possibilities how art can be re-conceptualized and executed. Besides that, a further deepening of the answer might be accomplished by a phenomenological interpretation of the inter-subjective phenomenon ‘artworld’.

During my second literature search for relevant sources regarding philosophical interpretations of Duchamp and phenomenological sources helpful in evaluating Duchamp from within that framework, I found a Master of Arts thesis by Alice Thorson titled “Marcel Duchamp: a phenomenological approach to art”, which was, of all places, submitted and approved at The School of Art at Northern Illinois University in 1981, the very same department I was taking a class on Duchamp for which I wrote this paper.[1]

After a careful reading I have to admit that the study is quite illuminating, thorough and basically trumps my own investigation. The structure of my paper will therefore be slightly different in that it will present Thorson’s findings, which I will try to test by some investigations of my own which she did not execute. Fortunately the volume of Duchamp’s artistic accomplishments, gestures, writings and interviews is extensive enough to execute the above intention. But before that we need a little outline of Husserl’s phenomenology, specially those features which will be relevant to the phenomenon art.

I. Phenomenology: epoché, eidetics, life-world

In this section I will present a somewhat skeletal overview of at least three basic phenomenological ideas, the first two of which–the epoché and eidetics–are better understood as philosophical techniques or procedures rather than ontological conclusions regarding fundamental features of reality. The third idea–the life-world–is about our experience of reality and, again, not about reality itself. As much as possible I will try to bring in the experience of art objects and of beauty into the discussion to clarify the ideas and create some initial understanding relevant to discussions later in the paper. Because Husserl’s ideas are all intimately and structurally interconnected, even define each other, it will be hard to keep his ideas in neat little boxes and not bring into play other fundamental Husserlian ideas like intentionality and intersubjectivity.

Epoché

The epoché is a subtle gestalt-switch in our perception of reality, going from our natural, naive, quotidian attitude about life and art, to a “suspension” or “bracketing” of this attitude. And not only our quotidian attitude is put out of play, but also any and all–or at least initially, most of–scientific, religious and metaphysical explanations. The idea is to come to a direct consideration of our experiences from within such experiences and bring new observations to language with the help of a vocabulary most appropriate to experience, without the help of constructs which come from outside. The idea is that we cease to look at the givens of life as if they are readymade and come from the outside, but that their existence is correlated with the manner in which we ourselves, in a mostly hidden subjective accomplishment, constitute them. The experience of an art object and the experience of beauty are not merely coming from outside ourselves but also have an active, intentional component which lies in our own subjective nature such that there is a congruency between the intentional perceiving act and the intended object as perceived. We are not passive blank slates upon which art objects, through the senses, can imprint their existence and beauty. We are active participants in the molding of such experiences by intending art objects as such and experience beauty (or the lack of it) as such. Or, as John Brough, from whom we will hear more later, expresses it. “In the epoche, then, the phenomenologist is no longer focused on the work of art as an object ‘in itself,’ but on how the work of art presents itself as a work of art in experience”. This attitude, or transcendental view, will “make possible the understanding of the subjectivity that functions anonymously in the natural attitude … ” (Brough, 1970, 29-30; italics in original; bold added).

If this point is grasped, one can see Husserl’s basic idea of the intentional structure of consciousness: consciousness is being conscious of–through a certain act–an intended object and is a process which goes through a few phases. Note that we might intend certain art objects as initially beautiful, but find ourselves frustrated in its fulfillment and might find the object actually ugly. This is because the dynamic aspect of intentional experience has the structural sequence of going from a) empty intending, to b) fulfilled intuiting, to c) relative stable identity over a certain time-span. For example, I might emptily intend something in the dark as a snake, but then cannot bring the intention to a fulfilled intuition of what I initially constitute as a snake, because it actually is a rope. This means I switched from the frustrated fulfillment of snake to emptily intending rope, and having that intention fulfilled such that a relative stable identity of rope is constituted. Such switches happen all the time in our experience of reality, but we are mostly not aware of the underlying mechanics.[2]

This point is of importance because a deeper understanding of Duchamp’s gestures might hinge on a correct understanding of the structure and dynamics of consciousness as investigated by Husserl and how Duchamp calibrates, inverts and even subverts these mechanics.

In short, the epoché is a subtle switch in attitude by which quotidian, scientific, religious and metaphysical explanations of experience and the manner in which they shape experience are set aside in order to make room for a more direct, careful exploration of experience from inside-out through which subsequently the intentional structure of consciousness can be discovered. In this manner many taken-for-granted claims about life and art become questionable, but also open to investigation as contingent accomplishments of human consciousness itself.

Eidetics

Eidetics, or the eidetic reduction, is a Husserlian technique to tease out the essence or eidos of a phenomenon by varying any and all aspects in one’s imagination and find out which aspects are, and which aspects are not, the sine qua non of both the experienced object and the experience of it. The procedure is also known as ‘imaginative free variation’ by which one can distinguish between ‘essential moments’ and ‘contingent parts’ of the phenomenon investigated. For example, one could wonder if the opening and the stem of a glass are essential or contingent elements of a glass. Through one’s imagination one can quickly figure out that a glass without stem can still function as a glass, but a glass without an opening not. Therefore, in phenomenologese, the stem is a contingent part and the opening an essential moment. Applied to art, the procedure of imaginative free variation would try to vary any and all of its aspects and see which are necessary components and which ones one could ‘drop’ as contingent. Here one could dwell on the ‘obvious’ example that an art object does not have to be beautiful and that beauty does not necessarily reside only in art objects. Because one can vary art objects as having beauty or not, beauty is a contingent part of art. And because one can vary beauty as residing in an art object or in nature, an art object is therefore a contingent aspect of beauty. Note that, though the example seems self-evident and not necessarily in need of clarification, one is able to explain its truth by way of applying imaginative free variation to sort out essence from contingency. Here again I like to stress the idea that Duchamp’s variations on art can be made more understandable if one grasps the technique of ‘imaginative free variation’, because it provisionally looks like that Duchamp, through his very imaginative variations, brought to consciousness many a hidden aspect of art of which the artworld was barely conscious and then showed either their necessity or non-essential nature, or at least made them questionable.

The life-world

The third Husserlian idea to put in place is the idea of life-world. The best way to introduce this idea is by way of an illuminating article by continental philosopher John Barnett Brough, titled “Art and Artworld: Some Ideas for a Husserlian Aesthetic”, in which he re-interprets, with the help of Husserl’s phenomenological idea of life-world, the institutional theory of art as developed by analytic philosopher of art George Dickie.[3]

Brough agrees with Dickie that works of art are not natural objects with intrinsic properties but are artifacts which have to attain the status of art object within the complex context of the values and practices of the artworld, a world comprised of artists, art critics, dealers, collectors, curators and the interested public. It is these people in their local or internationalized scenes which share and transmit the for-the-time-being acceptable answers to the questions of what art is, how it is presented and what might be said about it. Brough diverts from Dickie in calibrating the idea of ‘institutional’ by downplaying its organizational aspect and up-playing the idea of a shared, but not institutionalized “cultural practice”. Brough, formulating in Husserlian terms the necessary and sufficient possibility conditions for art to be, states that

… a cultural object can arise and can present itself as a cultural object … only within a particular world in which those creating the object and those to whom the object is presented form a community of praxis bound by a common goal. … The artworld as the cultural horizon “within which, for the individual, possible ways of understanding this culture are present” serves as the necessary and sufficient condition for the presentation of artifacts as works of art (Brough 1988, 36; Italics in original; bold added; quoting from Husserl, 1970).

Other aspects which Brough highlights in his article are the ideas that a) all people comprising the artworld fulfill different roles or vocations which both contribute to the constitution of this artworld and take the artworld as his or her given context; b) the artworld is really a communal, intersubjective creation in which each actor plays a partial role within the role of the whole community, however romantic individualistic or indifferently detached an actor might be. As Brough states, the artworld is a “nexus of individual subjects unified in a single cultural praxis” and is “a total, many-leveled intentional accomplishment of intersubjectivity” (Brough 1988, 37). And c) that the artworld is a thoroughly historical world in the sense that it is a mosaic unity of traditions which includes its entire cultural past and which unity provides the horizon within which innovations are possible, including the limit-seeking and -breaking innovative gestures by Duchamp.

II. Earlier phenomenological study of Duchamp

In the abstract of Alice Thorson’s MA thesis one can read that “[a]lthough interpretations of Duchamp and his works are many and varied, his ideas have yet to be considered in relation to those of phenomenology, the philosophical movement with which his development coincides, both chronologically and foundationally” (Thorson, 1981; hereafter AT). In this section I will present what seem to be Thorson’s main findings, which, with the help of the groundwork done in the previous section, should not be too arduous. Her findings come under four headings. First, she sees a direct connection between Duchamp and Symbolism as both were battling naturalistic presuppositions in aesthetics, which struggle went parallel with Husserl’s own struggle with naturalism in philosophy. Second, she makes the case that Duchamp and Husserl went through a similar sequence of four phases in their development. Third, she found in Duchamp’s life and work “a number of strikingly phenomenological elements” (AT, Abstract), three of which (eidetics, intentionality, non-dualism) she found important. And fourth, regarding Duchamp’s legacy, she states quite boldly that later artists “would instinctively recognize the importance of Duchamp’s phenomenological investigations, and in retrospect, Duchamp’s contributions become unified under the heading of a phenomenological approach to art” (AT, Abstract). In this section I will focus on the second and third headings, i.e. the parallel development between Duchamp and Husserl and Duchamp’s own non-formal phenomenological investigations.

Developmental parallels

Though I quickly perceived the non-formal phenomenological aspects of Duchamp’s work and was very glad to find Thorson’s study, I was initially quite skeptical about her claims about the developmental parallels between Husserl and Duchamp. After all, one is an artist and the other a philosopher working in entirely different media and I have not found the slightest indication of any direct or indirect influence on Duchamp by the work of the older Husserl.[4]

But after rereading her arguments and contemplating that both reacted to similar naturalist positions and ended up doing similar investigations, it could even be argued that the parallel between the two was necessarily based in the bare logic of the phenomena themselves with which they were dealing, regardless of the difference in media through which they worked. But this point might only become established after a thorough familiarization with the developmental arc of both innovators.

Returning to Thorson, she named the four parallel phases 1) Experiment, 2) Reintegration, 3) Transcendence, and 4) Return. The first phase was one of experiment and struggle, but maybe could have been better named refutation and rejection. Husserl’s first important development took place in his refutation of psychologism, which was an attempt at explaining logic by way of a naturalist psychology. Duchamp, after having created Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (Fig. 1), arguably a cubist masterwork, rejects cubism, a style still harboring vestiges of naturalism. In this struggle against naturalism Thorson also detects a struggle against dualism.

In the second phase Thorson sees a parallel between Husserl’s finding of the phenomenological reduction, the epoché, and Duchamp’s intention to “reduce, reduce, reduce …” (Duchamp quoted in AT, 98) his work from any concrete elements which resulted in what Thorson coins his short “mechanomorphic style” (AT, 91) and the presentation of the readymade. About the readymades she stated that its “effect of dispelling accepted preconceptions in art paralleled the effects of Husserl’s epoché in philosophy” (AT, 95). This is because both are quite radical switches from taking the world and art as merely given to the realization that there is a formative subjective component which might be more important in shaping our experience than previously acknowledged. This is the intentional structure of consciousness, which, because of the interaction and correlation between subject and object, is a step in overcoming dualism.

In the third phase the parallel is between on one side Husserl’s development of the eidetic reduction, i.e. the method to find essential structures and meanings through imaginative free variation, and on the other side Duchamp’s attempts to subjugate art to idea, which he very much realized in Large Glass (Fig. 2). As ideal meanings transcend their particular instantiations, so do the ideal elements in Large Glass resist identification with “empirical particulars” (AT, 98).

The last parallel, and this one clinched it for me, is about the return from the transcendental world of ideal meanings to the world as lived, the mundane world of everyday experiences, which after all, is the basis for any and all abstractions and idealizations we can construct. Maybe stirred by Martin Heidegger’s existential-phenomenological characterization of man’s Dasein as being-in-the-world (Heidegger, 1962)–that is, a part of man’s essence is the concrete situational ‘here/there’ of his world from which he cannot extract himself except in an imaginary way through mental abstraction–Husserl wrote a major analysis of the idea that in the end all our activities, even when oriented towards ideal meanings, scientific laws or philosophical necessities, they are all rooted within his or her communally constituted, intersubjective, thoroughly historical life-world (Husserl, 1970). Though Thorson under-presents Husserl’s idea of the life-world, she does develop how this return worked out for Duchamp. For her the pivotal year is 1934 when Duchamp executes this return with the conception of Box in Valise (Fig. 3), which gesture implied “a bow in the direction of art-permanence” (AT, 100), with which he confoundedly contradicted his status as an iconoclast.

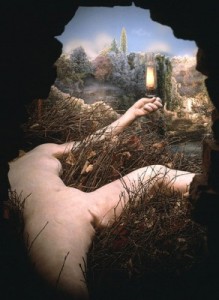

But the apotheosis of the return is Duchamp’s posthumously presented and still quite baffling Etant Donnés (trsl. Given; Fig. 4) comprised of a life-size old door with two peep holes through which one sees a three-dimensional tableau of a nude in a landscape. Thorson states that Etant Donnés is not a surrender to realism, nor a repudiation of his previous ideas, nor the effect of old age, nor a transformation because of looming death, all of which were proposed by other critics. The piece is an altogether logical outcome of the reconciliation of on one side ideas and the other side life. “The Etant Donnés signifies that like Husserl, Duchamp’s concern for ideas finds its ultimate resolution in a return to the lived-world as the basis of experience” (AT, 102).

In short, and as formulated in her abstract.

Careful examination reveals both artist and philosopher working through a similar sequence of ideas to arrive at comparable solutions. Both began with a struggle against dualism which they found couched in naturalist preconceptions. A realization of the intentionality of consciousness offered a solution to the initial subject/object division, while an awareness that meaning transcends its empirical presentation spurred them both on a search for ideal meanings. Ultimately each came to recognize that meaning inheres in the individual’s subjective experiencing of the everyday world (AT, Abstract).

III. The naive, non-formal phenomenology of Duchamp

Under the chapter title “Duchamp’s Phenomenological Approach to Art” Thorson unpacks further the very striking phenomenological aspects of Duchamp’s work. She especially focuses in on 1) Duchamp’s attitude towards art which very much resembles Husserl’s epoché; 2) his search for “eidetic essences”, 3) how intentionality confers meaning and binds subject and object and 4) the overcoming of duality in a qualified union. Once these aspects are fleshed out a new understanding is possible, one which could even provide a “unity and a new intelligibility” to Duchamp’s gestures with his conceptual event-objects.

Duchamp’s Epoché

Duchamp’s epoché can be found in his non-committal, aloof attitude towards politics, education, patriotism, religion, logic and many other aspects of society. He doesn’t believe in taking positions and tries to be beyond any of the pro or contra partisan positions. As far as art is concerned it looks like he is ‘bracketing’ a number of conventional ideas about art like the idea of progress in art; the artist’s sanctified role; art history and art’s alleged timeless power; taste and its cultivation in art education; and the institutionalized presentation of art in museums. Like Husserl’s concern to get “back to the things themselves” (Husserl quoted in AT, 119) Duchamp wants to be free from the limitations which come with ‘positions’ and conventional prejudices. He wants to go back to pure experience by breaking through the limitations which come with language and the manner in which language shapes experience.

Duchamp’s Eidetics

But, like Husserl, he is open for the existence of ideality, that is, the concept that in experience as well as in art, an idea or essence is always already operative or expressed and that this idea could be found through some sort of reduction, of which Husserl had a more explicit methodological awareness and Duchamp a more tacit, intuitive grasp. Thorson gives the example of how Duchamp went about to arrive at the essence of motion and how to depict that in artistic form. In this context Duchamp’s operative terms were reduction, stripping and denudation to conceive the essence of motion which culminated in his Nude Descending a Staircase, where naturalistic forms were stripped away and replaced by cubist abstractions with added lines and dots. As stated to Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp confirmed that with this piece he “was breaking the chains of naturalism forever …” (Cabanne quoting Duchamp as quoted in AT, 126). Thorson also discusses Duchamp’s use of “imaginative free variation”, being the methodology of the eidetic reduction and quotes him saying, “Any idea that came to me, the thing would be to turn it around and try to see it with another set of senses …” (Duchamp quoted in AT, 127). Initially his phenomenological investigations through free variations were directed at the essence of depicting motion in an artistic manner, but with the readymades the investigation shifted to the essence of art itself. Now his reductions and variations were targeting the then accepted attributes of art like “style, quality, originality, beauty, etc.” (AT, 132). These allegedly indispensable attributes were stripped away in the readymade, which were meant to have none of such even though others still did see beauty and originality.

Duchamp’s intentionality

Through this investigation of art with the readymade, what comes to the fore is, as discussed above, the intentional structure of experience. The art object is not established by external, objective standards about intrinsic qualities, nor by internal subjective, psychological reactions, but is established, or constituted, in the give and take between subject and object, in their polar relation. “Thus the readymade served to highlight the indissoluble unity between the object-as-intended and the subject’s intending-toward, and to reveal this relationship as the ultimate foundation for the determination of art-meaning” (AT, 132). It is Thorson’s contention that Duchamp is non-formally aware of this intentional structure in which the onlooker has a bigger role in establishing what art means than hitherto assumed.

The above point can be made a bit more explicit with the following example. We might initially emptily intend Fountain (Fig. 5) as an art object because it is presented to us with the claim that it is art. But, because so many aspects of art seem to have been stripped away in this object, we have to re-calibrate our set of tacit expectations regarding art by doing some quick imaginative free variations to test if the missing aspects are essential or not, and then either interpret Fountain as a silly or shocking hoax if we hold on to beauty, taste and style as essential to art, or we interpret the object as a significant, artistic conceptual event-object if we go along with Duchamp and toss them. A third alternative might be possible and that is to acknowledge Fountain as both showing and changing the boundaries of the definition and function of art, but still keep open a personal choice of what art might mean for oneself with the whole issue having become more explicitly open and elective. In this middle position Duchamp showed something about art, but did not necessarily destroy it as some have argued.

Photo of a duplicate.

Duchamp’s non-dualism

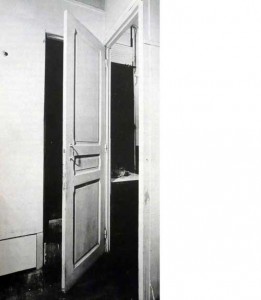

The last phenomenological aspect Thorson highlights is Duchamp’s overcoming of dualism–based on the inseparability of subject and object–not only in establishing the meaning and limits of art, but of meaning in general. His appreciation of complementarity of allegedly opposed positions; his acting out of the androgynous nature of the sexes through his alter ego Rrose Sélavy (trsl. Eros: Such-is-life; Fig. 6); his interest in the reconciliation of opposites in alchemy; his refutation of bivalent logic in Door, 11 Rue Larrey (Fig. 7), which door can be both open and closed at the same time; his eroto-maniacal preoccupation with sex; all these indicate a preference for non-dualism.

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Duchamp as phenomenologist?

In closing her chapter, Thorson thinks it wrong to qualify Duchamp as a phenomenologist. Too much what he did has no parallel in phenomenology and, I would add, many phenomenological investigations are too technical to find an equivalent in Duchamp.[5]

But phenomenology does provide “a tentative framework through which the variety and complexity of his activities gain coherence and greater intelligibility …” (AT, 140). I would classify Duchamp therefore as a non-formal, intuitive phenomenologist, because he was very accomplished in suspending and playing around in a phenomenological manner with art, but was not explicitly aware of the formal phenomenological manner he was doing so.

Because Duchamp’s conceptual event-objects were often more about art than art itself, the discussion about whether he created art or not could be settled by naming his gestures meta-artistic, which nicely captures the idea that his gestures were neither art nor non-art and had a built-in self-referential structure.

From cause to effect

Duchamp, as a non-formal phenomenological meta-artist, was able to liberate a similar critical distancing and imaginative capacity in his fellow artists and audience, which could be traced as the “Duchamp Effect”. As Thorson states, and I do agree, the phenomenological framework will help us in understanding his legacy, because “Duchamp’s legacy is a phenomenological approach to art” (AT, 141; italics in original; bold added) especially picked up and amplified in his friend John Cage.

Here I like to stress the idea, and add my own thoughts, that phenomenology can provide a unity of intelligibility to Duchamp’s art, as Thorson makes clear in different parts of her study. The unity consists in the idea that the Husserlian epoché and eidetics are closely intertwined and feed off each other. Critical distancing through suspension of assumptions will create a field of new possibilities and, other way around, being confronted with surprising instances of conceptual event-objects could lead, in different degrees, to critical distancing, even full-fledged entry into a transcendental attitude from which the interaction between oneself as an intending subject and its intended, constituted objects becomes a possibility (Meraud, 2010). Once one gets habituated within that attitude–which is not a given as one can slip out of it–a multitude of variations are possible and it looks like that Duchamp operated within the art world by inhabiting this attitude in a non-formal manner.

Also, based on the presented insights, one might evaluate possible critiques and re-interpretations of Duchamp’s work, for example the critiques coming from Clement Greenberg, Thomas Hess and Wayne Andersen.

Greenberg’s beef with Duchamp was that he thought he was too destructive for one’s fragile faculty of esthetic, contextualized expectation-cum-surprised satisfaction in relation to art, which for him was an essential ingredient of art appreciation to be finely cultivated (Greenberg, 1971). Greenberg has a point because phenomenology will show that we always already engage life and art with an interacting mix of tacit and explicit expectations, all set within, and to be explicated by, the dynamic sequence of a) intentional experience of emptily intending, to b) different degrees of fulfillment, culminating in c) stability, frustration or ambiguity. I think Greenberg had a fine, though conservative, appreciation for that dynamic. But again, Duchamp and his fellow avant-gardistas were not necessarily out there to destroy art come what may. They merely made such expectations and frameworks more explicit, questionable, investigatable and changeable. If they did so in an aesthetically tasteless manner or by shock and scandal is besides the point. Granted, I think some of what claims to be modern art is bad and tasteless, but at the same time the challenging of conventional standards of taste could only be effected by provocations through its opposite. And contrary to Duchamp’s statements that he had given up on art, he actually never did, and the presentation of Etant Donnés, which incorporated a vast amount of modern styles and vintage Duchampian gestures, made that point quite clear. Greenberg might have been shocked again, but I would be surprised if he would deny having learned anything from Duchamp.

My position here would be somewhere in between, in that we do not necessarily have to give up our own tacit and explicitly cultivated standards of aesthetics just because Duchamp happened to show their contingent, subjective nature, and we do not have to stick defensively to these standards like Greenberg, because modern art, even avant-garde art, is full of pleasant, aesthetic and thought-provoking surprises.

The above considerations should remind us also that a tendency towards an idealized interpretation of Duchamp should be resisted. Though Duchamp’s status since the 1960s has risen to that of patron saint of modern art, I find these older criticisms of Duchamp by Clement Greenberg and Thomas Hess still valid. And the recent quite severe and provocative deconstruction of Duchamp as an “overrated erotomaniac” by art historian Wayne Andersen in his study Marcel Duchamp: The Failed Messiah, is a welcome antidote. Andersen thinks, to quote him at his most provocative, that “Marcel Duchamp’s gift to artists was similar to the Marquis de Sade’s gift to sadists—relief from moral restraints, accountability, guilt, and shame” (Andersen, 2010, p. 3). In Andersen’s study it is not so much Duchamp himself who is to be blamed, but a section of the art world which had sanitized, elevated and aggrandized him as a messianic figure, whose “nihilism was eagerly adopted as artistic freedom” (Andersen, 2010, p. 5) and whose persona became more important than his art. Again, it is phenomenology which can elucidate the constitution of idealized narrative interpretations. Amongst many aspects, the idealization process includes the discarding of truly contingent, unimportant elements as well as suppressing essential, important ones. In Andersen’s view what got suppressed was Duchamp’s vulgarity, the second-rate nature of most of his art and his anti-feminism. Whether Andersen cut Duchamp to size a notch too far is for me an open question, but I think he does show that certain overlooked aspects of Duchamp’s persona and art are essential and have to be taken into consideration if one wants to arrive at the complex eidos Marcel Duchamp. The in-between position might be to acknowledge Duchamp as important and influential, but not to be infatuated with.

IV. Conclusion

It is Thorson’s contention, and mine too, that through understanding the epoché; the procedure of “imaginative free variation”; and the concept of life-world, we can better understand a) what Duchamp seemed to have accomplished as a conceptual artist creating thought-provoking event-objects; b) that he himself executed imaginative variations on art which unity becomes intelligible through understanding Husserl’s ‘imaginative free variation’; and c) that these variations set examples to other conceptually nimble artists to find their own unique variations.

Because a phenomenological assessment of Duchamp is, from a transcendental viewpoint, purely philosophical, it cannot in principle trump Marxist, psycho-analytic or critical art historical interpretations, because those pertain to the more empirical realms of sociology, psychology and history. A Marxist analysis of Duchamp’s personal position within the elitist upper class of American society might still result in relevant insights about Duchamp’s life and his art. And a psycho-analytic assessment of some of his formative experiences is not ruled out either. Here one can look at the possible long-term influence of his traumatic experience of having some of his most important works rejected by his fellow artists, as well as the often repeated hypothesis that he struggled with an incestuous tendency towards his sister. The first experience might have made him cynical about art and the second made him conflicted about sexuality. And, lastly, phenomenology cannot invalidate criticisms coming from Greenberg and Andersen. At best it can illuminate its procedures, but not set aesthetic standards.

In closing, it looks like to me that Duchamp’s “artistic conceptual event-objects” are meta-artistic phenomena which precariously balance on the cusp between art and philosophy such that his art, which is neither art nor non-art, can illuminate philosophy and other way around.

Endnotes

[1]. That a phenomenological approach to Duchamp was executed at NIU might not be a coincidence as NIU’s philosophy department in the 1970s and ’80s harbored accomplished continental philosophers like Lester Embree, who moved on to become one of the major organizers of the international movement of phenomenologists; Theodore Kisiel, a world-renowned expert on the early Heidegger; and Michael Gelven, who delved into literature, art and spirituality.

[2]. With ‘mechanics’ I do not mean to imply a mechanistic view, but rather something like the dynamic and structural logos of experience in which all parts are integrated and have some causal effect on each other and together compose a whole.

[3]. Brough drew on the following studies by George Dickie: Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis (Cornell University Press, 1974) and The Art Circle (Haven Publications, 1984).

[4]. If there might have been philosophical influences on Duchamp, besides the well-known influence of anarchist thinker Max Stirner, I would have looked at how Friedrich Nietzsche might have shaped Duchamp indirectly through artists like Hugo Ball of Cabaret Voltaire and closer to him, Francis Picabia, who both were familiar with and had embraced Nietzsche’s thought.

[5]. A logical next step would be to see if and how Heidegger’s existential-hermeneutic phenomenology might clarify further what Duchamp did.

Sources used and consulted

Andersen, Wayne. Marcel Duchamp: The Failed Messiah. Geneva, Switzerland: Èditions Fabriart, 2011. Print.

Brough, John B. “Art and Artworld: Some Ideas for a Husserlian Aesthetic”. Edmund Husserl and the Phenomenological Tradition: Essays in Phenomenology. Ed. Robert Sokolowski. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America, 1988. 25-45. Print.

Danto, Arthur. “The Artworld”. The Journal of Philosophy, 61/19 (Oct. 15, 1964): 571-84.

Demos, T. J. “Duchamp’s Labyrinth: ‘First Papers of Surrealism,’ 1942”. October, vol. 97 (Summer, 2001): 91-119.

Duchamp, Marcel. The Writings of Marcel Duchamp. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (Eds.). N.p.: Da Capo Press, n.d. Print. Originally published by Oxford University Press, 1973. Print.

Evans, J.C. et al. “Aesthetics”. Encyclopedia of Phenomenology. Ed. Lester Embree, et al. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1997. Print.

Greenberg,Clement. “Counter Avant-Garde” [1971]. In Marcel Duchamp in Perspective. Masheck, Joseph, ed., Da Capo Press, 2002. Pp. 122-33. Print.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1962, trans. by Macquarrie and Robinson. Print.

Hess, Thomas B. “J’Accuse Marcel Duchamp”. In Marcel Duchamp in Perspective. Masheck, Joseph, ed., Da Capo Press, 2002. Pp. 115-20. Print.

Hofmann, Werner. “Marcel Duchamp and Emblematic Realism”. In Masbeck, Joseph (Ed.). Marcel Duchamp in Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NY: Pretice-Hall, 1975. Print.

Hubregtse, Menno. “Robert J. Coady’s The Soil and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain: Taste, Nationalism, Capitalism, and New York Dada”. Revue d’art canadienne / Canadian Art Review 34 / 2 (2009). Web. 09 Feb. 2014.

Husserl, Edmund. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1970. Print.

Kisiel, Theodore. “Do It Yourself Phenomenology”. Hand-out. Philosophy 428, NIU, DeKalb, IL, Spring 2003.

Kosuth, Joseph. “Art after Philosophy”. Studio International (October, 1969).

Meraud,Tavi. “More Than Meets the Eye: Connections between Phenomenology and Art”. Postgraduate Journal of Aesthetics, Vol. 7, No. 3, December 2010. Web. 5 Feb 2014.

Moffitt, John F. Alchemist of the Avant-Garde: The Case of Marcel Duchamp. New York: State University of New York Press, 2003. Web. Googlebooks.

Ricoeur, Paul. Time and Narrative. 3 vols. transl. by Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984-88. Print.

Sokolowski, Robert. “The Logic of Parts and Wholes in Husserl’s Investigations”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 28/4 (Jun., 1968): 537-553

Thorson, Alice R. “Marcel Duchamp: a phenomenological approach to art”. MA Thesis Northern Illinois University, 1981. Thesis director Norman Magden. Print.

Thank you, Jim. I looked into your Zeit book a little and got the impression that you combine, at least at one level of your speculations, evolutionary theory with thermodynamics. I have a little essay on that, but not yet posted, titled “Gradiance: The Mother of all Reductions”. It’s based on: Schneider, Eric D.& Sagan, Dorion. 2005. Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics, and Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Superb essay on both Duchamp and especially Husserl. Don’t dive into Husserl without it (this essay). Worth its weight in gold for the bibliography alone.

Jim Blake – author: “Distill the Zeit” – AmazonKindle