Introduction

We know that the current monetary system is crisis-prone. We know that during the last big crisis in 2008 we skirted a total freeze-up and a possible break-down of the international banking system. We know that Wall Street was bailed-out and Main Street left to fend for itself. We know the system received some band-aids and was not re-set on a sound footing. And now we see another series of big booms and possible big busts, starting with the implosion of crypto-giant FTX in November 2022 and recently the bankruptcy of SVB.

Maybe a good quote to set the table for some warnings is the following from economists Dirk Bezemer and Michael Hudson (2016: 761):

An economy based increasingly on rent extraction by the few and debt buildup by the many is, in essence, the feudal model applied in a sophisticated financial system. It is an economy where resources flow to the FIRE sector [Finance, Insurance & Real Estate] rather than to moderate-return fixed capital formation [the productive economy]. Such economies polarize increasingly between property owners and industry/labor, creating financial tensions as imbalances build up. It ends in tears as debts overwhelm productive structures and household budgets. Asset prices fall, and land and houses are forfeited.

Different sources make it clear that we might be close again. Below is a little collection of economists and financial commentators ringing the bell with a postscript on the Silicon Valley Bank bankruptcy in March 2023.

Nouriel Roubini, aka Dr. Doom,

Dr. Doom in 2007 was on the forefront of warning the world that the time was ripe for a big correction, if not crisis. He’s back again.

The chairman and chief executive officer of Roubini Macro Associates, nicknamed Dr. Doom following his 2008 prediction, warned that anyone expecting a shallow US recession should examine the extensive debt ratios of corporations and governments.

Roubini added that as rates increase and debt servicing costs grow, “many zombie institutions, zombie households, corporates, banks, shadow banks and zombie countries are going to die” (Boughedda).

Later Roubini himself opened his analysis in an article with:

The world economy is lurching toward an unprecedented confluence of economic, financial, and debt crises, following the explosion of deficits, borrowing, and leverage in recent decades (Roubini).

“Recession is a certainty in 2023, but how much will it hurt India?”

This article in India Today carries lots of colorful graphs to see that the world will get into a recession in 2023 and that “various financial crises” will accompany it. When the World Bank and the IMF think there will be a recession this might be interpreted that it will actually pack out worse.

A new World Bank study shows that central banks across the globe raising interest rates to curb inflation may not be a good idea. This can likely lead to various financial crises along with the recession. “Global growth is slowing sharply, with further slowing likely as more countries fall into recession. My deep concern is that these trends will persist, with long-lasting consequences that are devastating for people in emerging markets and developing economies,” said World Bank Group President David Malpass (Sharma).

“Why The Banks Are Collapsing”

A reasonably good video comes from a somewhat alarmist web site analyzing five reasons why we can expect some or many big banks to collapse. The video is sponsored by a dubious company selling titles like ‘Lord’ and ‘Lady’ in Scotland.

1) Collateral Debt Obligations, 2) Corruption, 3) Collateral Loan Obligations, 4) Overconfidence, 5) Recession.

We can argue with this list as #5 Recession is more of an effect than a cause of bank behavior. And, though they mention it, Moral Hazard, the idea that banks expect that they will be bailed out anyway, should have its own entry. And what is totally missing is an analysis of the leading cause of financial crises and that is the allocation of easily created loans by commercial banks to the unproductive FIRE sector creating thereby asset bubbles which usually pop.

Trouble in Cryptoland

In November 2022 the crypto currency exchange platform FTX went bankrupt after a classic bank run with depositors withdrawing $6 billion. Crypto-giant and rival Binance might have triggered the run by withdrawing from FTX after revelations about a murky relationship between FTX and a sister company Alameda. Binance then thought of buying and bailing out the platform, but changed its mind in a day.

How far this bankruptcy will reverberate through cryptoland and the banking world is anyone’s guess but it is already dragging in its wake a few other outfits and the wipe-out of about $2 trillion in market value. And after FTX filed for bankruptcy hackers got away with $515 million. Some think this is a Lehman moment, which started the GFC in 2008, others compare it with the 2001 collapse of Enron. Regulators are expected to step in, which might scare more people into selling, creating more havoc, and justifying more regulation (Yaffe-Bellany; Wiki entry of FTX).

The inequality-crisis nexus: Its origin and application to India.

I stumbled upon prominent Indian economist Raghuram Rajan as one of the few who warned his peers at the 2005 Jackson Hole, Wyoming gathering of top bankers and their regulators, that the financial system had become potentially more crises-prone because of deregulation, innovation, dangerous incentives to bank managers and some other flaws (Rajan, 2006).

He said the rollout of complicated instruments such as credit-default swaps and mortgage-backed securities made the global financial system a riskier place. Indeed, he argued that such developments “may also create a greater – albeit still small – probability of a catastrophic meltdown” (Cooper).

Rajan was then chief economist at the IMF. Later he became governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Vice-Chairman at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and is now back in academia at the University of Chicago.

After the crisis he came out with an award-winning book, Fault Lines (2010), making the case that inequality had increased the debt burden of households. The logic was that households, in order to keep up with spending while income shrank, took on debt to make up for the difference. Rajan also thought that the US government was incentivizing mortgages too much, also leading to a growth in debt. For this he was criticized as it looked he was blaming the victims of the GFC. Summarizing Rajan’s position:

Much of the impetus for the current debate stems from Raghuram Rajan’s widely discussed book ‘Fault Lines’ (2010). Rajan argues that low and middle income consumers have reduced their saving and increased debt since income inequality started to soar in the United States in the early 1980s. This has temporarily kept private consumption and employment high, but it also contributed to the creation of a credit bubble. With the downturn in the housing market and the sub-prime mortgage crisis starting in 2007, the overindebtedness of U.S. households became apparent and the debt-financed private demand expansion came to an end in the ‘Great Recession’ of 2008/9 (Van Treeck, 2013: 421).

How this nexus might apply to India is next and starts with a picture of inequality in India.

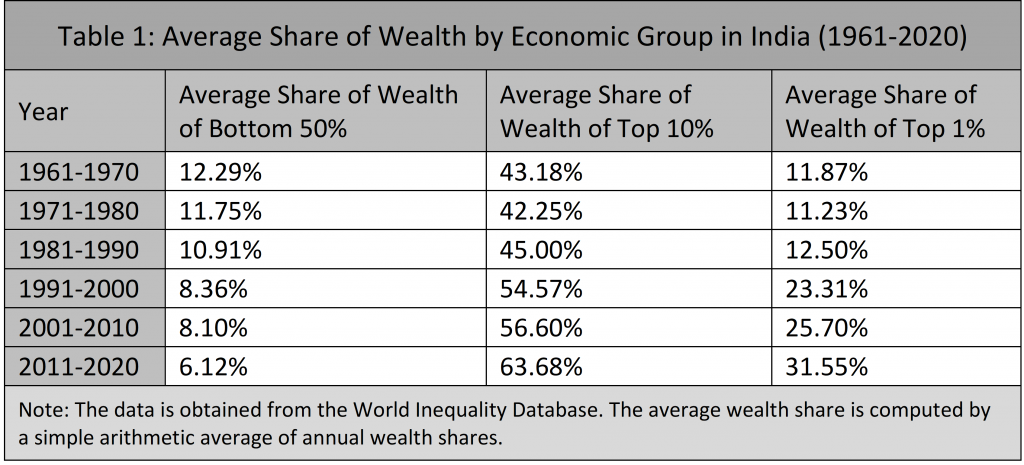

For example, data from the recently published “World Inequality Report 2022” suggests that inequality – of both income and wealth – in India kept increasing in the last few decades and that this trend has continued even in recent years. In particular, after 1990, the share of the national income of the top 10% and top 1% has consistently increased while the share of the national income of the bottom 50% has consistently declined.

The article comes with a table which makes the trend over six decades painfully clear (Gathak, 2022).

Next step is to look at the trend in bank lending in the form of retail loans and mortgages.

According to data released by RBI, the bulk of the increase in bank lending has been on account of retail loans, with credit card outstanding, consumer durables and loans against fixed deposits being the new drivers of growth in FY22.

. . . . Individuals continue to borrow for consumption even as corporations have deleveraged and paid their loans (Shetty, 2022).

But what are the causes of this increase of indebtedness? Increased consumer optimism? Easier access to loans? Or the relative income hypothesis? This hypothesis is based on the idea that consumption patterns are related to the perception and valuation of one’s relative socio-economic position in one’s environment. It combines the desire of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ during boom times and trying to keep up with your own previous peak consumption during downturns. The relative income hypothesis is a component of the Rajan hypothesis of causally connecting inequality with financial fragility.

Though I have anecdotal and observed evidence from the US for Rajan’s hypothesis, I am not sure how it would work out in India. The first thing to find is some correlation between increased inequality in India and increased indebtedness, and then see if causal connections can be made. But this project is too big to pursue here.

Postscript

Meanwhile in March 2023 a potentially humungous crisis was temporarily averted after two US banks went bankrupt and were taken over by different authorities. Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in California ($209b) and Signature Bank in New York ($118b) are now the second and third biggest bank failures in US history after the record-setting failure of Washington Mutual ($307b) in 2008. Though 97% of deposits at SVB and 90% at Signature were not insured, the US government regards the crisis as a systemic risk and will guarantee all deposits in newly formed ‘bridge banks’. Throughout the crisis stock markets stayed relatively calm, but some banks took big hits with shares of Republican Bank going down 60%. The price of safe-haven gold increased about 5%.

Some Tremors in India

SVB’s troubles created also concern in India because many Indian start-ups and high-net-worth individuals have big accounts at SVB.

Indian startups that have millions of dollars stuck with the troubled Silicon Valley Bank are waiting for business hours in the US to resume Monday and could withdraw all their money from the bank en masse. The only thing that could stop that is if the US government manages to find a buyer for the beleaguered bank, founders said (Barik).

Little did anybody know that US regulators would step in with guarantees.

Ellen Brown

Again, what is next is anybody’s guess, though some of our allies in the monetary reform movement think it can be dire.

For example Ellen Brown of the Public Banking Institute warns that again we are facing the collapse of the derivatives house of cards. This time the derivatives used as a hedge against interest rate changes will come into play. She writes about “The Interest Rate Shock” which will ripple through the system.

Interest rate derivatives are particularly vulnerable in today’s high interest rate environment. From March 2022 to February 2023, the prime rate (the rate banks charge their best customers) shot up from 3.5% to 7.75%, a radical jump. Market analyst Stephanie Pomboy calls it an “interest rate shock.” It won’t really hit the market until variable-rate contracts reset, but $1 trillion in U.S. corporate contracts are due to reset this year, another trillion next year, and another trillion the year after that.

A few bank bankruptcies are manageable, but an interest rate shock to the massive derivatives market could take down the whole economy (Brown).

Steve Keen

Another warning comes form Australian economist and author Steve Keen. He blames the actions of the Fed in raising interest rates while ignoring its effects on the financial sector. He thinks that the Fed uses models in which debt, banks and money are ignored. The causal chain is that increased interest rates will diminish the value of bonds, of which many banks have massive amounts on their books.

Meanwhile, in the real world, rising interest rates on government bonds can cause banks to go insolvent. SVB was the canary in the coal mine here, but the factor that brought it undone is shared by all financial institutions, because government bonds are a major component of their assets. When interest rates rise, bond values fall, and this can drive financial institutions into insolvency—where their Liabilities exceed their Assets (Keen).

In his own Minsky Model he shows that the financial sector as a whole might get into negative equity territory if interest rates hit 5%. That is, the whole sector can go belly-up. Though he states his scenario is more hypothetical and educational than a real-world plausibility, the lesson he wants to convey is that,

It’s The Fed that deserves to be roasted instead, for attempting to manage the financial system using models that ignore banks, debt, and money.

Michael Hudson

Famed author and economist Michael Hudson addresses both of the above mentioned dangers, i.e. a) the effect of increased interest rates on the value of bonds and in turn its effect on the equity position of banks, and b) the looming danger of derivatives. On the interest rate he states that,.

Prices are plunging for bonds, and also for the capitalized value of packaged mortgages and other securities in which banks hold their assets on their balance sheet to back their deposits.

The result threatens to push down bank assets below their deposit liabilities, wiping out their net worth – their stockholder equity.

Like others, he wondered “why the Fed doesn’t simply bail out banks in SVB’s position”, but that question has just been answered by the regulators with their decisive intervention fully guaranteeing all deposits.

The issue with derivatives he thinks is the “larger elephant in the room”.

Volatility increased last Thursday and Friday. The turmoil has reached vast magnitudes beyond what characterized the 2008 crash of AIG and other speculators. Today, JP Morgan Chase and other New York banks have tens of trillions of dollar valuations of derivatives – casino bets on which way interest rates, bond prices, stock prices and other measures will change.

According to Hudson we are getting into really dangerous territory:

So far, the stock market has resisted following the plunge in bond prices. My guess is that we will now see the Great Unwinding of the great Fictitious Capital boom of 2008-2015. So the chickens are coming home to roost – with the “chicken” being, perhaps, the elephantine overhang of derivatives fueled by the post-2008 loosening of financial regulation and risk analysis.

By the way, the two above economists have written some of the most hard-hitting and provocative criticisms of how the economics discipline is mis-theorized by their peers through ignoring the role of money, banks and the money creation process. From Hudson we have J Is For Junk Economics, and Keen wrote Debunking Economics.

Alternatives

In the six years after the 2008/9 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) the monetary reform movement has attained far-reaching results in promoting breakthrough monetary theories, especially the credit creation theory of money and banking, and in proposing reform policies based on empirical findings and computer models.

Many central and commercial banks admitted the truth about money creation and through citizen’s initiatives many popular assemblies had to discuss the findings and proposals. In Switzerland it even came to a referendum.

Our ideas are still spreading and are picked up in many countries to the extent that monetary reform organizations have been started. Even so, main stream economists, politicians and policy think tanks are resisting our findings or stay blissfully ignorant of them. Hopefully this half-panic around SVB’s downfall will create questions about the current crisis-prone, unsustainable monetary system and awaken the vision that a more stable, more equitable and less indebted system is possible.

Sources

Anonymous. 2022. “Why The Banks Are Collapsing: The Coming Economic Crisis”. Moon YouTube Channel, Nov 2022.

Barik, Soumyarendra. 2023. “Indian startups with millions of dollars stuck in Silicon Valley Bank weighing en masse withdrawal”. Indian Express, 13 March 2023.

Bezemer, Dirk & Hudson, Michael. 2016. “Finance is not the economy: Reviving the conceptual distinction ”. Journal of Economic Issues, 50/3: 745-768.

Boughedda, Sam. 2022. “Nouriel Roubini, “Dr. Doom,” Expects a Severe, Long and Ugly Recession – Bloomberg”. Investing.com, 20 Sept 2022.

Brown, Ellen. 2023. “The Looming Quadrillion Dollar Derivatives Tsunami”. The Web of Debt Blog, 13 Mar 2023.

Cameron, Cooper. 2015. “6 economists who predicted the global financial crisis”. In the Black, 7 July 2015.

Gathak, Maitreesh et al. 2022. “Trends in Economic Inequality in India”.The India Forum, 19 Sept 2022.

Hudson, Micheal. 2017. J Is For Junk Economics: A Guide To Reality In An Age Of Deception. Dresden, Germany: ISLET Press. (Amazon)

Hudson, Micheal. 2023. “Why the Banking System is Breaking Up“.12 Mar 2023.

Keen, Steve. 2011. Debunking Economics: The Naked Emperor Dethroned? London: Zed Books. (Amazon)

Keen, Steve. 2023. “Silicon Valley Bank: The Fed’s Role in its Downfall”. Patreon, 11 Mar 2023.

Rajan, Raghuram G. 2006. “Has finance made the world riskier?.” European Financial Management, 12/4: 499-533.

Rajan, Raghuram G. 2010. Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Roubini, Nouriel. 2022. “The Unavoidable Crash“. Project Syndicate, 2 Dec 2022.

Sharma, Samrat. 2022. “Recession is a certainty in 2023, but how much will it hurt India?” India Today, 12 Oct 2022.

Shetty, Mayur. 2022. “Individuals borrow more, corporates deleverage”. Times of India, 5 Sept 2022.

Trading Economics. 2022. Graph of Households Debt in India in Percentage of GDP, 2009-2022. Derived from the Bank of International Settlements.

Van Treeck, Till. 2014. “Did inequality cause the US financial crisis?” Journal of Economic Surveys, 28/3: 421-448.

Wiki entry: FTX (Company)

Yaffe-Bellany, David. 2022. “Embattled Crypto Exchange FTX Files for Bankruptcy”. New York Times, 11 Nov 2022.

Extra: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ftx-leaked-balance-sheet-visualized/

Excellent