Abstract.

In terms of states-of-consciousness one could differentiate within Krishnamurti’s mystical experiences a spirito-logical sequence. In other words, K went through multiple, discernible phases of spiritual awakening with a step-by-step logic going from low to higher realms. The focus of this paper is to interpret these statements within a Theosophical framework. The primary sources to make the point are 1) K’s own statements about his extraordinary experiences and 2) Theosophical glossaries.

K started out as a young man with mundane thoughts and desires (Kama-Manas), who then was inspired by a higher principle (Buddhi) to control his lower inclinations. After the start of the painful Process, he would have spiritual visions of meta-empirical realms and beings. The Process purified K to the extent he could be overshadowed by a higher being, Maitreya. More in private he experiences intense moments of mysticism to which he gave the name The Beloved (Atman). Later he would have even deeper and vaster experiences of “Benediction” (Sat-chit-ananda) arguably moving in the realm of Atman-Brahman. Then the whole series is crowned with his experience of the source of all energy (Parabrahm).

In conclusion I claim to have shown that, first, K’s states of consciousness are different enough that they can be expressed in different concepts, and secondly, that K was aware of these differences and was the first one to suggest non-technical concepts. Thirdly, as skilled Theosophists can do, parallels can be found with Theosophical, Sanskrit-based terminology

Introduction

There exists a tendency to separate Krishnamurti’s life into two segments. The first segment is his early life as a Theosophical spokesperson and candidate to become the vehicle for a next Avatar or World Teacher to manifest itself through. The second segment is as an independent teacher focused on helping people to understand the workings of their mind with a discourse free from any Theosophical notions about occult forces or meta-empirical beings.

The break between the two is in 1929, when Krishnamurti, in a dramatic speech dissolved the Star in the East, an organization which helped prepare for the coming World Teacher, and emphatically disavowed the concept and title. Some would add a transitional period between 1929 and 1933, in which he purged his new vocabulary from Theosophical ideas, had extensive exchanges with his audience regarding Theosophical issues, resigned from the TS, said farewell to his two Theosophical guardians, Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater who passed away in 1933 and 1934 respectively, and claimed to have lost most of his memories of the preceding years (Lutyens, 1976: 280).

The Vacant Boy or phased development

Nevertheless, there are two possibilities to interpret Krishnamurti’s spiritual life as not involving a dramatic break. One is based on remarks from an older Krishnamurti himself and the other is a Theosophical perception worked out in this paper.

In later life, when his younger years would become the subject in private conversations, Krishnamurti brought up the idea of “the boy” (referring to himself) not having been conditioned by Theosophy, because he was from the beginning vacant and absent-minded and not taking Theosophy serious. In a conversation with Mary Lutyens she reports that he wondered,

. . . why had he been picked out by Leadbeater from the other boys on the beach? What was the quality of ‘the boy’s’ mind then? Was he a freak? What had protected him all these years? Why was it that ‘the boy’, subjected to all that adulation and Theosophical indoctrination, had not become corrupted or conditioned? (Lutyens, 1983: 170)

In short, if he never took Theosophy serious and was never affected by its ideas, there could not have been a break with it. His mind just had been vacant all the time and never went through dramatic changes. The question arises whether Krishnamurti, because he did not remember much from his early years, was merely projecting his later state of enlightenment back into his past. After all, he is on record in his early years as an articulate and passionate Theosophist and believer of his erstwhile calling.

The other interpretation is that Krishnamurti went through multiple, discernible phases of spiritual awakening which can be tracked in the terminology of Theosophical anthropology with its seven principles making up the human being, and Theosophical theology with its differentiation of a few shadings of divinity. In this narrative there is no sharp break either, merely the gradual fading of the Theosophical worldview in favor of a more experiential and non-technical vocabulary, interchangeable though with a more Theosophical terminology. The aim of this paper is to flesh out this case.

The Terminology

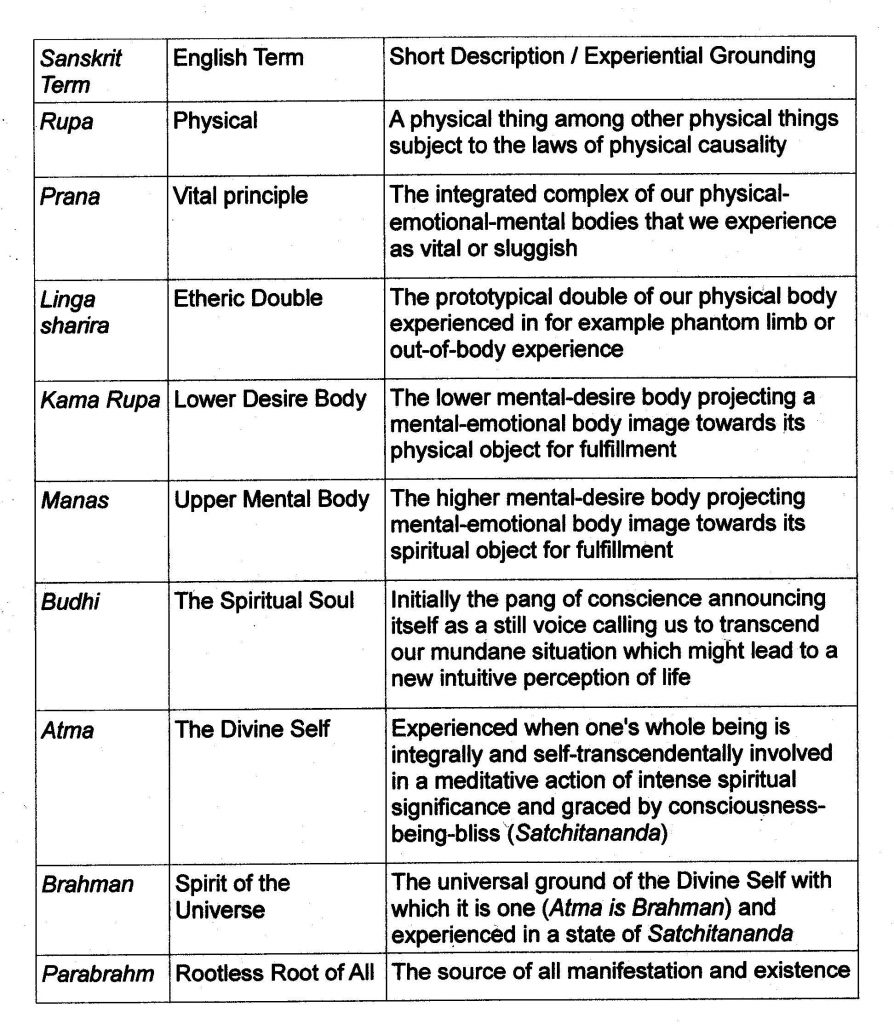

The following is a table of the Sanskrit and English terms, which I have extracted from several Theosophical sources (Blavatsky, 1892; Besant, 1909; Purucker, 1999). I added descriptions in a more phenomenological and experiential language to make a bridge to the level of lived experiences of mystics, especially Krishnamurti .

In this schema the combined Atmâ-Buddhi-Manas form the Monad or reincarnating trinity of the three highest, immortal principles. Below this trinity are the four lower, mortal principles (Rupa, Prana, Linga sharira and Kama rupa) and above the trinity are Brahma, the spirit of the universe, and Parabrahm, the absolute root of all existence. These are the basic terms which will come into play in interpreting Krishnamurti ‘s spiritual experiences.

Fig. 1. Table of Sanskrit and English terms for aspects

of human beings and levels of consciousness.

The Chronology

a) In the years leading up to 1922 Krishnamurti was often critical, rebellious, doubtful of his expected role as vehicle for the coming World Teacher, even sometimes depressed. One could say that he was subjected to regular, mundane experiences of Kama-Manas (lower thoughts and desires) with sometimes some Buddhi (inspirational conscience) poking through (Lutyens, 1976: 111-2 & 138-9).

b) This attitude was radically altered by his re-conversion or re-dedication to his mission inspired by a message received in Sydney in June 1922 from one of the Masers in the Theosophical pantheon, Mahatma Kuthumi. With a touch of skepticism Krishnamurti ‘s biographer and long-time friend Mary Lutyens wrote that the message was “‘brought through’ by Leadbeater”, i.e., next to Annie Besant, Krishnamurti ‘s spiritual and allegedly clairvoyant guardian with a line of communication with the Mahatmas. The opening sentences of the message read:

Of you, too, we have the highest hopes. Steady & widen yourself, and strive more & more to bring the mind & brain into subservience to the true Self within (Idem: 147).

Inspired by the message Krishnamurti wrote five weeks later that “I am going to get back my old touch with the Masters & after all that’s the only thing that matters in life & nothing else does” (Idem: 152. Italics in original). One could say that in a moment of vision and subsequent dedication the Buddhi principle was prevailing over his Kama-Manas.i

c) From then on Krishnamurti engaged in a regular regime of meditation. This could be conceived as the stabilizing of the Buddhic in silence by subsuming the lower bodies. Of his intention Krishnamurti wrote that

” . . . I had to harmonize all my other bodies with the Buddhic plane . . . To harmonize the various bodies I had to keep them vibrating at the same rate as the Buddhic . . .” (Idem: 152, 158).

d) Residing in August 1922 in Ojai, California, Krishnamurti experienced the start of the painful and dramatic Process. This could be conceived as if the Mahatmas were purging Krishnamurti ‘s body through occult means while K himself was mostly absent in a state of out-of-body experience (OBE). Krishnamurti also had experiences of his Kundalini rising, i.e. the awakening of his spiritual energies in the Root Chakra at the base of the spine and rising towards the Crown Chakra at the top of the head (Idem: 166 ).

Occasionally, when Krishnamurti ‘s soul was OBE (“went off”), a child-like sub-personality would express itself about the pain the body was going through. In Theosophy this is called the “physical elemental” and is a part of one’s Kama Rupa (lower desire body) connected to the physical body (Idem: 165, 175-7, 188).

e) After a year and a half, and back in Ojai again, the Process culminates in the opening of both the Crown and Third Eye Chakras, making it possible for Krishnamurti to have conscious communion with the Mahatmas and attain a clear certainty about his mission (Idem: 186). At this moment one could say that the Buddhic principle had fully overcome and subdued the Kama-Manas.

f) Then Krishnamurti experienced initially a traumatic, but finally a very transformative experience. On his way to India in November 1925 to attend the golden jubilee of the TS, he received news of the death of his brother and life companion Nityananda. In and through the mourning process Krishnamurti seemed to have purged the last vestiges of doubt and attachments. It was a deepened vision born out of suffering. Krishnamurti also expressed that he was unified in spirit with Nityananda (Idem: 220).

g) On December 28, 1925 occurred the first manifestation of Maitreya in Adyar (now Chennai), India at the grounds of the international headquarters of the Theosophical Society during a meeting of the Star in the East. Many claimed, and even watched clairvoyantly, that Maitreya spoke through Krishnamurti, something he himself confirmed afterwards (Lutyens, 1976: 223). The openness and trust involved in being overshadowed were enabled by K’s stable Buddhic state of awareness, making it possible for a realized Mahatma to temporally ‘take over’ Krishnamurti’s vocal cords at that level.

h) Around 1927 Krishnamurti starts to re-frame his mystical-developmental arc with the intentionally vague term “my Beloved“. For Krishnamurti his Beloved was the ultimate goal to be united with, like attaining a mountain top or entering a flame (Idem: 247). As long as this goal had not yet been attained one could conceive this as the Buddhic sighting of Atman, i.e. the individualized spiritual soul has the vision of the all-pervasive divine self.

i) Krishnamurti becomes the Beloved in moments of intense mysticism. He sees the Beloved as everywhere and within everything. For Krishnamurti the Beloved was “the open skies, the flower, every human being” including all the Mahatmas, even Maitreya and Buddha, “and yet it is beyond all these forms” (Idem: 249). Here it could be argued that some fusion of the Buddhic with the Atman was established and he could be named an Ātma-jñānin, or knower of Ātma.

These pronouncements became the stepping stones for K to go beyond Theosophy into his own unique interpretation of his states of mind, though Krishnamurti’s statements also became stumbling blocks for the more doctrinaire Theosophists in their evaluation of him, especially surrounding the question whether he was fulfilling the World Teacher Project or not.

j) By 1961, and maybe even earlier, Krishnamurti has deep experiences of ‘benediction,’ ‘otherness,’ and ‘immensity.’ He referred to these experiences early on in his Notebook as “that fullness of Il L.”, i.e. Il Leccio, the name of a Tuscan villa belonging to Krishnamurti’s friend Vanda Scaravelli (Krishnamurti, 1976: 11-12). This might have been the place where these experiences started when he visited it on a regular basis just after WWII. This experience seems to have been unexpectedly coming and going, though in differing intensities.

Again, in more Sanskrit terminology one could say he was experiencing Sat-chit-ananda, the combination of Being (Sat), Consciousness (Cit) and Bliss (Ananada), and, maybe best caught in the phenomenologically re-arranged phrase ‘blissful consciousness of being’.

k) Krishnamurti’s state of high intensity meditation culminates one night in the middle of November 1979 in reaching “the source of all energy”, which he perceived as “the ultimate, the beginning and the ending and the absolute” as he stated in a specially dictated account of that momentous event. In Hindu philosophy Atma (the soul) is equated with Brahm (God). As Krishnamurti was arguably at that level of consciousness already, it could very well be that the ‘source’ was beyond Brahm, i.e. Parabrahm, the highest, supreme principle, the root of all that exists.

On the other side it has to be mentioned that in the same statement he cautioned his readers that his experience “must in no way be confused with, or even thought of, as god or the highest principle, the Brahman, which are the projections of the human mind out of fear and longing, the unyielding desire for total security” (Lutyens, 1983: 237-8). With this seemingly ultimate experience the sequence comes to an end.

Discussion

So far the identifiable steps Krishnamurti took on his spiritual-developmental arc and the possible Sanskrit terms to describe them. Excluded in this enumeration are the states of consciousness relevant to Krishnamurti as a teacher, which had its own developmental stages.

What has been gained with this differentiation? First of all it has to be noted that, though words fall short in giving complete descriptions, these states of consciousness are different enough that they can be expressed in different concepts. Secondly, that Krishnamurti was aware of these differences and was the first one to suggest the appropriate non-technical concepts. Thirdly, as skilled Theosophists and probably Sankritists can do, parallels can be found with Theosophical and Sanskrit terminology.

The fact that he was aware of these experiences and could describe them afterwards indicates that something like a ‘self,’ or something ‘self-same,’ was enduring during these experiences, at least from the experience itself up to the moment of having them written down. For me this also indicates that something implicitly self-aware in the experience became explicitly so in the wording and that memory had some function in this transition.

This has to be mentioned because Krishnamurti would often claim that his kind of experiences would leave no trace in memory. In the context of this paper such pondering is not that relevant, though Krishnamurti’s mystical experiences are grist for the mill of an existential-phenomenological interpretation to be pursued in other venues.

Bibliography

Besant, Annie. 1909. The Seven Principles of Man. Theosophical Manual No. 1. Revised and corrected edition. London: The Theosophical Publishing Society

Blavatsky, H. P. 1892. The Theosophical Glossary. London: Theosophical Publishing Society.

Krishnamurti, Jiddu. 1976. Krishnamurti’s Notebook. New York: Harper & Row.

Lutyens, Mary. 1976. Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening. New York: Avon Books.

——-. 1983. Krishnamurti: The Years of Fulfillment. New York: Avon Books.

Purucker, G. de & Knoche, Grace (eds). 1999. Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary. Electronic Version. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press.

Source

Source

This small paper is a reworked section from “Two Theosophical Views on Krishnamurti: One Sympathetic, One Critical“. Alpheus, 3 Oct 2019. The origin of this account was in several discussions conducted with Theosophists connected to the Theosophical Society in America (TSA), on awareness and its connection to implicit and explicit self-awareness and how such ideas might apply to Krishnamurti. We used a lot of Theosophical concepts to further elucidate K’s experiences and states of mind. Many years later this article was presented as a paper, titled “Krishnamurti’s Spiritual Development from a Theosophical Perspective”, at the Indian Philosophical Congress (IPC), 96th and 97th Joint Session, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, on 22 December 2023.